Como Park Area History

Included below:

Como Park: A Historical Tour of One of Saint Paul’s “Beauty Spots”

Author: Sharon Shinomiya

Como Woodland Outdoor Classroom Advisor and local resident. 8-2008Millions of people visit Como Park every year and this has been the case since the park was developed more than 120 years ago. This land, set aside as a refuge from city life before the city of Saint Paul even reached this area, has seen many changes.

A Walk Through the Woods and Beyond – Como’s Early History

Take a walk through the wooded area in Como Park south of Horton Avenue and east of Hamline Avenue and you may notice traces of Como Park’s past. Before you enter, stop and imagine the land as it looked before European settlement and development: an oak savanna with prairie grasses, gentle hills, low, swampy areas and gravelly ridges; in the distance, a shallow lake or two.

Watch as the Mdewakanton Dakota make their way through this area between the park and the fairgrounds from their home in the south to harvest wild rice at lakes further north. Listen for the squeaky wheels of the oxcarts carrying French traders on the Red River Trail to the south.

Go back in time even further and witness the huge bodies of water left behind as glaciers retreated after the last Ice Age. For a long time, this area was covered by Glacial Lake Hamline, which extended from near the St. Paul campus of the University of Minnesota to the northwest end of Lake Como and down south past Hamline University and as far as Summit Avenue.

- A Historical Tour of one of Saint Paul's "Beauty Spots"

- Walking History Tour of Como Park (scroll to the bottom to see this one)

Como Park: A Historical Tour of One of Saint Paul’s “Beauty Spots”

Author: Sharon Shinomiya

Como Woodland Outdoor Classroom Advisor and local resident. 8-2008Millions of people visit Como Park every year and this has been the case since the park was developed more than 120 years ago. This land, set aside as a refuge from city life before the city of Saint Paul even reached this area, has seen many changes.

A Walk Through the Woods and Beyond – Como’s Early History

Take a walk through the wooded area in Como Park south of Horton Avenue and east of Hamline Avenue and you may notice traces of Como Park’s past. Before you enter, stop and imagine the land as it looked before European settlement and development: an oak savanna with prairie grasses, gentle hills, low, swampy areas and gravelly ridges; in the distance, a shallow lake or two.

Watch as the Mdewakanton Dakota make their way through this area between the park and the fairgrounds from their home in the south to harvest wild rice at lakes further north. Listen for the squeaky wheels of the oxcarts carrying French traders on the Red River Trail to the south.

Go back in time even further and witness the huge bodies of water left behind as glaciers retreated after the last Ice Age. For a long time, this area was covered by Glacial Lake Hamline, which extended from near the St. Paul campus of the University of Minnesota to the northwest end of Lake Como and down south past Hamline University and as far as Summit Avenue.

Mammoths and most likely, mammoth hunters, roamed here long ago. As the glaciers melted and the glacial lakes drained, forests moved in: the pine forests to the north and the broadleaf forests, full of white oak and deer, to the east and south. Ojibwe and Dakota hunted and clashed here.

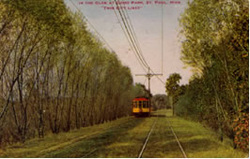

Come back to the present, and as you enter the woodland, you’ll see two paths. One, on the diagonal from the corner of Horton and Hamline, follows the now-removed section of Como Avenue that met this intersection. The other penetrates straight into the woodland canopy following the old Como-Harriet Streetcar Line. Old rail ties from the line were still visible along the edges of that trail – at least they were before the installation of a new bicycle and pedestrian path.

The 110-year-old streetcar bridge over old Beulah Lane has been rebuilt as part of the new path. The stone streetcar station that replaced an earlier wooden one still stands on the corner of Lexington and Horton, fully renovated, an office and meeting spot for community members.

Follow old Como and look carefully to your left, into the woods. You can see the ruins of the cascades and pool built by the Works Progress Administration in 1936 under the direction of W. Lamont Kaufman, Superintendent of Parks. Trees and shrubs now hide the limestone slabs that form its outline, but its grassy pool is clearly visible.

Come back to the present, and as you enter the woodland, you’ll see two paths. One, on the diagonal from the corner of Horton and Hamline, follows the now-removed section of Como Avenue that met this intersection. The other penetrates straight into the woodland canopy following the old Como-Harriet Streetcar Line. Old rail ties from the line were still visible along the edges of that trail – at least they were before the installation of a new bicycle and pedestrian path.

The 110-year-old streetcar bridge over old Beulah Lane has been rebuilt as part of the new path. The stone streetcar station that replaced an earlier wooden one still stands on the corner of Lexington and Horton, fully renovated, an office and meeting spot for community members.

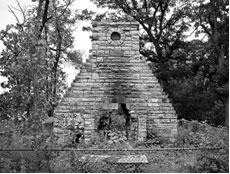

Follow old Como and look carefully to your left, into the woods. You can see the ruins of the cascades and pool built by the Works Progress Administration in 1936 under the direction of W. Lamont Kaufman, Superintendent of Parks. Trees and shrubs now hide the limestone slabs that form its outline, but its grassy pool is clearly visible.

Further along Como, across from the former gravel pit that is now McMurray Field, you’ll come to a clearing, in the middle of which sits a stone fireplace, neglected and crumbling behind a chain-link fence. The fireplace was built and dedicated in 1936 as part of the Joyce Kilmer Arboretum, donated by the Joyce Kilmer Post of the American Legion. Superintendent Kaufman belonged to this post. The Arboretum’s plaque with Kilmer’s famous poem Trees is long gone.

Look across the playing fields to the railroad tracks and beyond and you will see the structures of the old Northern Pacific Railway’s Como Shops, now Bandana Square. Railroads and their supporting industries employed one quarter of Saint Paul’s work force in the 1880s. The new residential neighborhoods popping up along Como Park’s borders in the mid-1880s offered convenient housing that may have appealed to many of the hundreds of employees of the Como Shops.

Further south, just past the Como Shops, the Koppers Coke Plant operated from 1916 to 1979. The plant produced coke, gas, ammonia, tar and benzol and employed hundreds of workers. You may not wish to imagine the fumes that on occasion must have wafted over the park from this plant.

Continue through this largest remaining untamed area of Como Park and you’ll come to the Como Pool, an amenity donated to the city in 1963. What you won’t see is the County Workhouse, an anomaly that was located on the southeastern corner of the park from 1881 to 1960. In 1881, as the city waited for better economic times to develop Como Park, the workhouse was erected here, “out in the woods,” far beyond residential development. As early as 1887, the newly formed park board protested its placement in the park and eleven years later the city attorney ruled its placement illegal. Its location in the park wasn’t completely without benefit: prisoners provided free labor for projects and upkeep throughout the park. Still, it took more than half a century to remove it. This same area was eyed as a possible location for a permanent, larger zoo in 1930. It is being eyed now as the site for a new water park.

This Land Becomes a Park

Como Park began its life as a public park in 1873. In the 1840s, Charles Perry, a native of the Swiss-Italian Alps, owned the land around Lake Como and grew potatoes on it. In 1848, Perry moved north and homesteaded land at Lake Johanna. Henry McKenty, the “king of real estate dealers”, came to Saint Paul in 1851. He took advantage of the boom in real estate in the 1850s to buy and sell land in Saint Paul and around Lake Como. Lake Como is named after the famous Lake Como in the Italian Alps.

Though it seems logical that Perry named the lake after his birthplace, it is McKenty who is credited with renaming Sandy Lake as Lake Como in 1856. (McKenty also named Lakes Johanna and Josephine after his wife and daughter.) McKenty used his own money to build a road that zigzagged across land he didn’t own, from Saint Paul’s downtown, to bring people out to the lake and his “Como Out-Lots,” a resort community platted on the east side of the lake.

The road was finished in 1857, the same year the red brick Adler Hotel opened on the east shore of the lake and the same year McKenty’s fortunes took a nosedive with the faltering economy. After the Civil War, three hotels operated along the shores of Lake Como and J. C. Burbank ran an omnibus to the lake three evenings a week during the summer.

H. W. S. Cleveland – Park as Respite From City Life

Parks were fashionable in the 1870s, and Horace W. S. Cleveland, a renowned landscape architect, urged Saint Paul and other cities to set aside land for parks before land became scarce and costs climbed too high. According to Cleveland, city leaders should “regard it as a sacred duty to preserve this gift [the landscape’s natural features] which the wealth of the world could not purchase, and transmit it as a heritage of beauty to your successors forever.”

The Minnesota Legislature authorized a bond issue of up to $100,000 in 1872 for the city of Saint Paul to acquire land for a major public park. After the land for Como Park was purchased in 1873, an economic downturn caused citizens to question the wisdom of this expenditure, but the city held on to the land.

Development of the park, however, would be stalled for the next fourteen years. Finally, when the economy improved and more funds became available, in 1887 the city allocated money to develop Como Park into a landscape park. Cleveland, who at the time served as Minneapolis’ Landscape Architect, was hired to design Saint Paul’s parks and parkways, including Como Park.

Look across the playing fields to the railroad tracks and beyond and you will see the structures of the old Northern Pacific Railway’s Como Shops, now Bandana Square. Railroads and their supporting industries employed one quarter of Saint Paul’s work force in the 1880s. The new residential neighborhoods popping up along Como Park’s borders in the mid-1880s offered convenient housing that may have appealed to many of the hundreds of employees of the Como Shops.

Further south, just past the Como Shops, the Koppers Coke Plant operated from 1916 to 1979. The plant produced coke, gas, ammonia, tar and benzol and employed hundreds of workers. You may not wish to imagine the fumes that on occasion must have wafted over the park from this plant.

Continue through this largest remaining untamed area of Como Park and you’ll come to the Como Pool, an amenity donated to the city in 1963. What you won’t see is the County Workhouse, an anomaly that was located on the southeastern corner of the park from 1881 to 1960. In 1881, as the city waited for better economic times to develop Como Park, the workhouse was erected here, “out in the woods,” far beyond residential development. As early as 1887, the newly formed park board protested its placement in the park and eleven years later the city attorney ruled its placement illegal. Its location in the park wasn’t completely without benefit: prisoners provided free labor for projects and upkeep throughout the park. Still, it took more than half a century to remove it. This same area was eyed as a possible location for a permanent, larger zoo in 1930. It is being eyed now as the site for a new water park.

This Land Becomes a Park

Como Park began its life as a public park in 1873. In the 1840s, Charles Perry, a native of the Swiss-Italian Alps, owned the land around Lake Como and grew potatoes on it. In 1848, Perry moved north and homesteaded land at Lake Johanna. Henry McKenty, the “king of real estate dealers”, came to Saint Paul in 1851. He took advantage of the boom in real estate in the 1850s to buy and sell land in Saint Paul and around Lake Como. Lake Como is named after the famous Lake Como in the Italian Alps.

Though it seems logical that Perry named the lake after his birthplace, it is McKenty who is credited with renaming Sandy Lake as Lake Como in 1856. (McKenty also named Lakes Johanna and Josephine after his wife and daughter.) McKenty used his own money to build a road that zigzagged across land he didn’t own, from Saint Paul’s downtown, to bring people out to the lake and his “Como Out-Lots,” a resort community platted on the east side of the lake.

The road was finished in 1857, the same year the red brick Adler Hotel opened on the east shore of the lake and the same year McKenty’s fortunes took a nosedive with the faltering economy. After the Civil War, three hotels operated along the shores of Lake Como and J. C. Burbank ran an omnibus to the lake three evenings a week during the summer.

H. W. S. Cleveland – Park as Respite From City Life

Parks were fashionable in the 1870s, and Horace W. S. Cleveland, a renowned landscape architect, urged Saint Paul and other cities to set aside land for parks before land became scarce and costs climbed too high. According to Cleveland, city leaders should “regard it as a sacred duty to preserve this gift [the landscape’s natural features] which the wealth of the world could not purchase, and transmit it as a heritage of beauty to your successors forever.”

The Minnesota Legislature authorized a bond issue of up to $100,000 in 1872 for the city of Saint Paul to acquire land for a major public park. After the land for Como Park was purchased in 1873, an economic downturn caused citizens to question the wisdom of this expenditure, but the city held on to the land.

Development of the park, however, would be stalled for the next fourteen years. Finally, when the economy improved and more funds became available, in 1887 the city allocated money to develop Como Park into a landscape park. Cleveland, who at the time served as Minneapolis’ Landscape Architect, was hired to design Saint Paul’s parks and parkways, including Como Park.

Plans made by Cleveland in the late 1880s emphasized the preservation and development of natural features in the park. According to him, parks were places for people to escape city life, to stroll or boat, ice skate or ride horses, to picnic, play and appreciate nature’s beauty. The landscape gardener, Cleveland believed, had “no other duty than to serve as the high priest of Nature” and he should “only dare to touch with very reverent hands, the symbols through which she addresses her worshippers.” Many roads and the Hamline picnic grounds were completed during Cleveland’s tenure.

The Park Matures – Frederick Nussbaumer Years

John Estabrook served as Superintendent of Parks for one year before Frederick Nussbaumer, a gardener hired by the park in 1887, began his thirty-year tenure in 1891. Nussbaumer had worked in London’s Kew Gardens and in Paris. Though Nussbaumer agreed with Cleveland’s philosophy of naturalistic parks, he also thought parks should provide opportunities for organized, active recreation, an idea that was popular at this time.

The Park Matures – Frederick Nussbaumer Years

John Estabrook served as Superintendent of Parks for one year before Frederick Nussbaumer, a gardener hired by the park in 1887, began his thirty-year tenure in 1891. Nussbaumer had worked in London’s Kew Gardens and in Paris. Though Nussbaumer agreed with Cleveland’s philosophy of naturalistic parks, he also thought parks should provide opportunities for organized, active recreation, an idea that was popular at this time.

Under Nussbaumer’s leadership, the layout of the park was completed and many recreational amenities were added. The floral display gardens and the lily pond once known as the Aquarium were developed. The Mannheimer Memorial was erected in 1906 atop what was later known as “peony” hill. A wide flight of brick and marble stairs led up to the wooden pergola. Under its pergola stood a sparkling marble fountain designed by famous architect Cass Gilbert. The memorial connected the lily pond to gardens on the top of the hill.

The Nelumbium Pond and Rockery, now known as the Frog Pond, was completed in 1911. An outdoor Banana Walk, or Palm Avenue, featuring tropical plants in the summer, was located at the base of the east picnic grounds hill where Lexington Parkway is now. The tropical plants overwintered in greenhouses in the park. In 1915, the impressive, glass-domed Conservatory opened, fulfilling Nussbaumer’s long-held dream for Como Park.

The Saint Paul City Railway reached the Como neighborhoods in 1892. Six years later the railway had permission to construct their line through the park in exchange for building the Lexington Parkway bridge, the footbridge over the tracks, and the lakeside pavilion, where many band concerts were held both summer and winter.

The Nelumbium Pond and Rockery, now known as the Frog Pond, was completed in 1911. An outdoor Banana Walk, or Palm Avenue, featuring tropical plants in the summer, was located at the base of the east picnic grounds hill where Lexington Parkway is now. The tropical plants overwintered in greenhouses in the park. In 1915, the impressive, glass-domed Conservatory opened, fulfilling Nussbaumer’s long-held dream for Como Park.

The Saint Paul City Railway reached the Como neighborhoods in 1892. Six years later the railway had permission to construct their line through the park in exchange for building the Lexington Parkway bridge, the footbridge over the tracks, and the lakeside pavilion, where many band concerts were held both summer and winter.

A 1911 trolley guide described the “restful rural loveliness of [Como Park’s] natural landscape, with its hills and dales, groves and meadows, and its charming lake nestling in the encircling arms of its treeclad hills.” Visitors could find paths and miles of drives, boating, a Japanese garden, fountains, lawns and flowerbeds. The trolley was an important way for the “masses” to visit the park.

“The great mass of people enjoy flowers. They also pay for the parks,” Nussbaumer wrote in his article An Ideal Public Park in 1902. He believed there should be no “keep off the grass signs” and that parks should be available to both the “nature-loving enthusiast and frugal workman” and provide both facilities for recreation and “objects of attractiveness.”

The Como Zoo began informally in 1897 with the donation of three deer. Thomas Frankson, real estate developer and former lieutenant governor, donated some buffalo. Similar donations swelled zoo inhabitants to well over 100 in 1930, and included buffalo, deer, elk, bears, coyotes, red foxes, rabbits, goats, raccoons, porcupines, a badger, woodchucks, monkeys, guinea pigs, opossums, rats, alligators, pheasants, pigeons, crows, a chicken hawk and owls. An old iron arch structure with a curved top, built by Nussbaumer, became the first zoo cage when it was erected in the buffalo pasture and covered with netting. Its curved top determined the design of later cages.

“The great mass of people enjoy flowers. They also pay for the parks,” Nussbaumer wrote in his article An Ideal Public Park in 1902. He believed there should be no “keep off the grass signs” and that parks should be available to both the “nature-loving enthusiast and frugal workman” and provide both facilities for recreation and “objects of attractiveness.”

The Como Zoo began informally in 1897 with the donation of three deer. Thomas Frankson, real estate developer and former lieutenant governor, donated some buffalo. Similar donations swelled zoo inhabitants to well over 100 in 1930, and included buffalo, deer, elk, bears, coyotes, red foxes, rabbits, goats, raccoons, porcupines, a badger, woodchucks, monkeys, guinea pigs, opossums, rats, alligators, pheasants, pigeons, crows, a chicken hawk and owls. An old iron arch structure with a curved top, built by Nussbaumer, became the first zoo cage when it was erected in the buffalo pasture and covered with netting. Its curved top determined the design of later cages.

In 1904, a Japanese garden was created on the shores of Cozy Lake, a smaller, shallower lake that was located where the golf course is now, and was connected by a canal to Lake Como. The garden was developed in response to a gift made by Dr. Rudolph Schiffman, an original member of the Saint Paul Park Board in 1887. He donated a collection of Japanese shrubs and trees he purchased at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Dr. Schiffman had earlier donated the Schiffman Fountain, modeled on one in Barcelona, Spain, and installed near the lake and pavilion.

In the early twentieth century, a playground movement swept the country and Como Park. Ball fields were built on the northwest corner of the picnic grounds and tennis courts were added near the Conservatory. A large playground area and open-air theater north of Cozy Lake appear on Nussbaumer’s 1905 design for the park, though it is not clear how much of it was actually built. A map included in a 1917 trolley guide shows a running track, playground, shelter pavilion, wading pool and swimming pool north of Cozy Lake.

Changes in the Park

Superintendent of Parks Nussbaumer retired in 1922. George Nason succeeded him in 1924 and set to work paving the parkways for the droves of automobiles now motoring around the park. Adequate parking for all those vehicles became a problem, as it still is now.

Nason believed that parks were “educational and should be kept distinctly beautiful in character.” According to him elements of beauty included broad lawns framed by trees, large masses of shrubs and beautiful flowers. Activities in the park included skating, tennis, horseshoes, soccer, ball games, pavement dances, toboggan slides, horse races and dog races, and of course, picnicking. Some events drew crowds of tens of thousands.

In the early twentieth century, a playground movement swept the country and Como Park. Ball fields were built on the northwest corner of the picnic grounds and tennis courts were added near the Conservatory. A large playground area and open-air theater north of Cozy Lake appear on Nussbaumer’s 1905 design for the park, though it is not clear how much of it was actually built. A map included in a 1917 trolley guide shows a running track, playground, shelter pavilion, wading pool and swimming pool north of Cozy Lake.

Changes in the Park

Superintendent of Parks Nussbaumer retired in 1922. George Nason succeeded him in 1924 and set to work paving the parkways for the droves of automobiles now motoring around the park. Adequate parking for all those vehicles became a problem, as it still is now.

Nason believed that parks were “educational and should be kept distinctly beautiful in character.” According to him elements of beauty included broad lawns framed by trees, large masses of shrubs and beautiful flowers. Activities in the park included skating, tennis, horseshoes, soccer, ball games, pavement dances, toboggan slides, horse races and dog races, and of course, picnicking. Some events drew crowds of tens of thousands.

The Conservatory held spring flower shows, fall chrysanthemum shows and December poinsettia shows. A perennial border bloomed north of the Mannheimer Memorial. In 1930, a rose garden, and iris and peony garden were added. The iris garden was entered through an ornamental iron arch supported by Doric columns.

The bridle path was improved, and Como’s new golf course, the city’s third public course, opened, one of the many courses springing up all over this golf-crazed country. Planning began for a new, improved, larger zoo.

The bridle path was improved, and Como’s new golf course, the city’s third public course, opened, one of the many courses springing up all over this golf-crazed country. Planning began for a new, improved, larger zoo.

During the 1920s, problems with maintaining lake water levels in both Cozy and Como Lakes continued. Many years earlier, in 1895, the city dredged Lake Como to increase its depth from five to fifteen feet to combat swampiness. Drought and leakage caused the city to pump thousands of gallons of water into the lakes. In 1921 new electric pumping machinery was installed. In 1923, the city went so far as to drain the entire lake to patch leaky areas. Finally, the city gave up and in 1925 the leaky northern portion of Lake Como was filled and dammed. Cozy Lake dried up, the Japanese garden disappeared, and the area became the new golf course. With the addition of the golf course, a large portion of the park became devoted to organized, active recreation.

From the W. Lamont Kaufman Years to Today

W. Lamont Kaufman became Superintendent of Parks in 1932 and served for the next thirty-three years. The Depression years brought another period of development to Como Park. From 1935 to 1941, the Works Progress Administration completed many projects in the park, especially in the zoo. Projects included Monkey Island, the main zoo building and the bear grotto. Pony rides were offered in the park in the 1940s and amusement rides opened after World War II.

As early as 1955 city officials recommended closing the zoo, but a citizen’s volunteer committee fought to keep it open. They succeeded, and the zoo was even able to add to its collection. The zoo hired its first director in 1957. The primate house opened in 1969, and after the completion and funding of a Master Plan for Como Zoo in the mid-1970s many more new zoo buildings were constructed. A new Japanese garden opened in 1979 and a new focus on education prompted the offering of garden classes at the Conservatory.

Following 1981 Como Park Master Plan recommendations, many roads were removed from the park to reduce traffic congestion and de-emphasize the impact of the automobile in and around the park. Lexington Parkway was rerouted and the pavilion was reconstructed using old blueprints.

Today, Como Park continues to be a well-loved and much-visited city and regional park. We have the foresight of our forebears to thank for it. And that wooded area? It is in the process of becoming the Como Woodland Outdoor Classroom, a preserved and enhanced woodland for the enjoyment of the public and the scientific education of area students

W. Lamont Kaufman became Superintendent of Parks in 1932 and served for the next thirty-three years. The Depression years brought another period of development to Como Park. From 1935 to 1941, the Works Progress Administration completed many projects in the park, especially in the zoo. Projects included Monkey Island, the main zoo building and the bear grotto. Pony rides were offered in the park in the 1940s and amusement rides opened after World War II.

As early as 1955 city officials recommended closing the zoo, but a citizen’s volunteer committee fought to keep it open. They succeeded, and the zoo was even able to add to its collection. The zoo hired its first director in 1957. The primate house opened in 1969, and after the completion and funding of a Master Plan for Como Zoo in the mid-1970s many more new zoo buildings were constructed. A new Japanese garden opened in 1979 and a new focus on education prompted the offering of garden classes at the Conservatory.

Following 1981 Como Park Master Plan recommendations, many roads were removed from the park to reduce traffic congestion and de-emphasize the impact of the automobile in and around the park. Lexington Parkway was rerouted and the pavilion was reconstructed using old blueprints.

Today, Como Park continues to be a well-loved and much-visited city and regional park. We have the foresight of our forebears to thank for it. And that wooded area? It is in the process of becoming the Como Woodland Outdoor Classroom, a preserved and enhanced woodland for the enjoyment of the public and the scientific education of area students

Source List:

Andrew J. Schmidt, Planning St. Paul’s Como Park: Pleasure and Recreation for the People, Minnesota History 58/1, Spring 2002, pp. 40-58

Aaron Isaacs and Bill Graham, The Como-Harriet Streetcar Line: A Memory Trip Through the Twin Cities (The Donning Company Publishers, 2002)

Como Park Master Plan, 1981

“The City Itself a Work of Art:” A Historical Evaluation of Como Park for the City of St. Paul, Minnesota, draft for St. Paul Division of Parks and Recreation, August 1996, The 106 Group Ltd.

Patricia Murphy and Gary Phelps, Swamps, Farms, Boom or Bust: Como Neighborhood’s Colorful History, Ramsey County History, 19/1, 1983-84, pp. 13-22

The Enterprising Salesman and the Old Road to Lake Como, Ramsey County History, 6/1, Spring 1969, pp. 14-16

Virginia B. Kunz, A Day in the Life Henry McKenty, Minnesota History, 56/4, Winter 1998-99, pp. 235-237

William H. Tishler and Virginia S. Luckhardt, H.W.S. Cleveland, Pioneer Landscape Architect to the Upper Midwest, Minnesota History, 49/7, Fall 1985, pp. 281-291

Biography, History, Roster of Joyce Kilmer Post, No. 107, American Legion, Saint Paul, Minnesota, 1930

H.W.S. Cleveland, Public Parks, Radial Avenues, and Boulevards. Outline Plan of a Park System for the City of St. Paul, Comprised in Two Addresses Delivered Before the Common Council and Chamber of Commerce, June 24, 1872 and June 19, 1885

Fred Nussbaumer, An Ideal Public Park, The Minnesota Horticulturist, 30/3, March 1902

George L. Nason, Visiting Around St. Paul Parks, extracted from St. Paul Dispatch, July 4 – December 1, 1932

Samuel W. Pond, The Dakota or Sioux in Minnesota As They Were in 1834 (Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul, 1986)

Glimpses Into Early Local History: How Como Park Nearly Was Lost to St. Paul, 1916

Susan Davis Price, Minnesota Gardens: An Illustrated History (Afton Historical Society Press, 1995)

Warren Upham, Minnesota Geographic Names: Their Origin and Historic Significance (Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, 1920)

A 20-Year Vision for Como Lake: The Como Lake Strategic Management Plan Report, Como Lake Strategic Plan Committee, July 2001 (Capitol Region Watershed District)

Como Park Historical Resources Inventory, City of Saint Paul Division of Parks and Recreation, August 1995

St. Paul Daily News, St. Paul Soccer Players to Have Their Own Field, August 16, 1925; Permanent, Larger Zoo Planned for Como Park, June 15,1930; Fight for New Workhouse Here Dates Back to 1887, December 7, 1930; Como Zoo Began with 2 Rabbits, Now has 163 Varied Denizens, May 11, 1930

Daily Globe, May 12, 1901, p. 24

St. Paul Pioneer Press, Como has New Sunken Pool, May 24, 1936; Bad End of a Busy Life, August 11, 1869; Physician to the Stars … of Como Zoo, July 5, 2008

St. Paul Dispatch, Lake Johanna Pioneers, August 2, 1950

How to See the Twin Cities, 1911, http://reflections.mndigital.org

The Twin Cities Today, 1917, http://reflections.mndigital.org

Duke Addicks, Interview, July 23, 2008

www.comozooconservatory.org

www.ci.arden-hills.mn.us

Andrew J. Schmidt, Planning St. Paul’s Como Park: Pleasure and Recreation for the People, Minnesota History 58/1, Spring 2002, pp. 40-58

Aaron Isaacs and Bill Graham, The Como-Harriet Streetcar Line: A Memory Trip Through the Twin Cities (The Donning Company Publishers, 2002)

Como Park Master Plan, 1981

“The City Itself a Work of Art:” A Historical Evaluation of Como Park for the City of St. Paul, Minnesota, draft for St. Paul Division of Parks and Recreation, August 1996, The 106 Group Ltd.

Patricia Murphy and Gary Phelps, Swamps, Farms, Boom or Bust: Como Neighborhood’s Colorful History, Ramsey County History, 19/1, 1983-84, pp. 13-22

The Enterprising Salesman and the Old Road to Lake Como, Ramsey County History, 6/1, Spring 1969, pp. 14-16

Virginia B. Kunz, A Day in the Life Henry McKenty, Minnesota History, 56/4, Winter 1998-99, pp. 235-237

William H. Tishler and Virginia S. Luckhardt, H.W.S. Cleveland, Pioneer Landscape Architect to the Upper Midwest, Minnesota History, 49/7, Fall 1985, pp. 281-291

Biography, History, Roster of Joyce Kilmer Post, No. 107, American Legion, Saint Paul, Minnesota, 1930

H.W.S. Cleveland, Public Parks, Radial Avenues, and Boulevards. Outline Plan of a Park System for the City of St. Paul, Comprised in Two Addresses Delivered Before the Common Council and Chamber of Commerce, June 24, 1872 and June 19, 1885

Fred Nussbaumer, An Ideal Public Park, The Minnesota Horticulturist, 30/3, March 1902

George L. Nason, Visiting Around St. Paul Parks, extracted from St. Paul Dispatch, July 4 – December 1, 1932

Samuel W. Pond, The Dakota or Sioux in Minnesota As They Were in 1834 (Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul, 1986)

Glimpses Into Early Local History: How Como Park Nearly Was Lost to St. Paul, 1916

Susan Davis Price, Minnesota Gardens: An Illustrated History (Afton Historical Society Press, 1995)

Warren Upham, Minnesota Geographic Names: Their Origin and Historic Significance (Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, 1920)

A 20-Year Vision for Como Lake: The Como Lake Strategic Management Plan Report, Como Lake Strategic Plan Committee, July 2001 (Capitol Region Watershed District)

Como Park Historical Resources Inventory, City of Saint Paul Division of Parks and Recreation, August 1995

St. Paul Daily News, St. Paul Soccer Players to Have Their Own Field, August 16, 1925; Permanent, Larger Zoo Planned for Como Park, June 15,1930; Fight for New Workhouse Here Dates Back to 1887, December 7, 1930; Como Zoo Began with 2 Rabbits, Now has 163 Varied Denizens, May 11, 1930

Daily Globe, May 12, 1901, p. 24

St. Paul Pioneer Press, Como has New Sunken Pool, May 24, 1936; Bad End of a Busy Life, August 11, 1869; Physician to the Stars … of Como Zoo, July 5, 2008

St. Paul Dispatch, Lake Johanna Pioneers, August 2, 1950

How to See the Twin Cities, 1911, http://reflections.mndigital.org

The Twin Cities Today, 1917, http://reflections.mndigital.org

Duke Addicks, Interview, July 23, 2008

www.comozooconservatory.org

www.ci.arden-hills.mn.us

THANK YOU

The Como Woodland Advisory Committee wishes to thank Sharon Shinomiya for researching and authoring this this page. Sharon Shinomiya © 2009.

The Como Woodland Advisory Committee wishes to thank Sharon Shinomiya for researching and authoring this this page. Sharon Shinomiya © 2009.